As greenhouse gas emissions continue to drive global warming, the public and private sectors are increasingly investing in carbon offsets.

Carbon offsets allow companies and governments to cancel their own emissions by supporting projects that eliminate or reduce emissions of an equal amount of greenhouse gases.

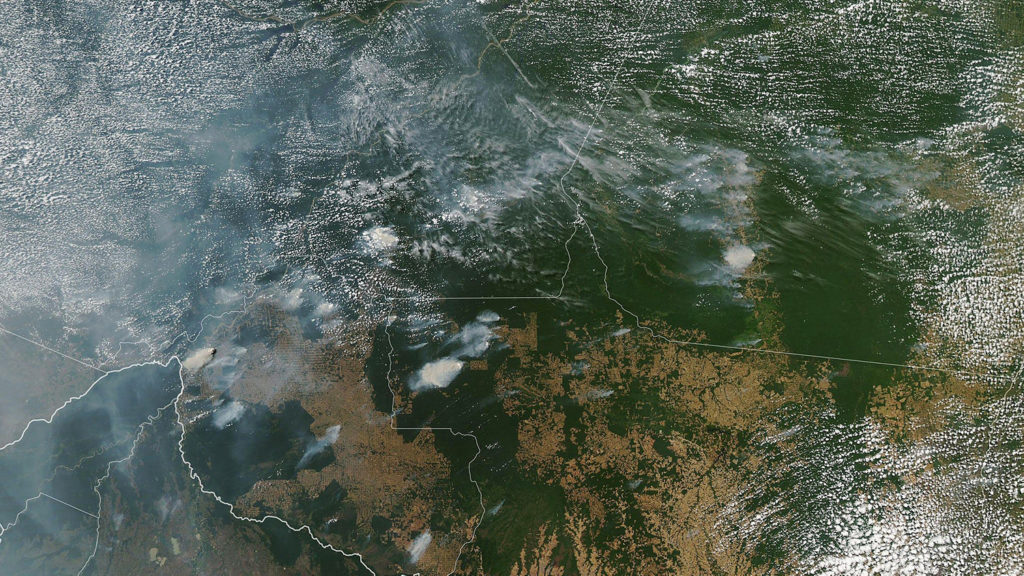

Many projects focus on promoting forest conservation. Forests play a vital role in climate change mitigation because they capture and store greenhouse gases.

Unfortunately, the world has lost about a billion acres of forest since the 1990s due to agriculture, livestock grazing, mining, drilling, urbanization, and more.

Countries adopted the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) framework as part of the Paris Agreement to incentivize forest conservation.

The primary goal of the Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to “well below” 3.6°F above pre-industrial levels, and also to pursue efforts to limit warming to 2.7°F.

More than 140 countries, including the United States, have agreed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as close to zero as possible. The United States has set a goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

As countries work to reduce their emissions in line with the national goals they have set under the Paris Agreement, they can use REDD+ to do so.

The REDD+ framework also allows greenhouse gas emitters to pay for reducing deforestation and degradation, primarily in tropical landscapes in the Global South, as a way to reduce emissions.

Emitters (whether companies or governments) typically exchange their payments for “carbon offsets,” which act as permits or moral license to continue emitting the equivalent amount of greenhouse gases.

While reducing emissions through carbon offsets is important to achieving global net-zero emissions goals, the effectiveness of the REDD+ framework remains in question.

Erin SillsEdwin F. Conger Professor of Forest Economics at NC State, along with other researchers, studied REDD+ projects that generate carbon offsets for the voluntary market and found that many projects overestimate their impact.

A study carried out by Sills and collaborators shows that only 6% of total carbon offsets prepared by 18 REDD+ projects in five tropical countries are valid.

We recently spoke with Sills to learn more about the challenges impacting REDD+ projects around the world. Learn more below.

Climate change, markets and policies

The success of a REDD+ project ultimately depends on its ability to conserve forests, a difficult task in today's world. "Forest conservation is challenging because there are external factors that cannot be easily controlled," Sills said.

One of those factors includes climate change, which is increase the frequency, intensity and duration of forest fires and tropical storms. Both effects can negatively affect trees that are part of carbon offset projects.

When trees within a carbon offset project are burned or felled, for example, they release stored carbon into the atmosphere. Those emissions must be deducted from the project's benefits. "All that carbon goes up in smoke," Sills said.

In 2021, for example, the Bootleg Fire consumed approximately 414,000 acres across southern Oregon. About 100,000 of those acres belonged to a carbon offset project containing about 3.3 million metric tons of carbon.

But climate change is not the only external factor capable of negatively impacting REDD+ and other forest carbon offset projects, according to Sills. Market forces and government policies can also play a role.

“It is difficult to conserve a forest if the price of palm oil skyrockets and the alternative use of that forest is oil palm, or if a new government is elected that does not prioritize forest conservation,” he said.

Drain

Aside from climate change and other external factors, leaks can also affect REDD+ and other forest carbon offset projects. This phenomenon occurs when projects cause greenhouse gas emissions to move from one place to another.

Direct leakages occur when people or companies within project areas relocate their activities to different areas, resulting in greater deforestation in those areas. These activities usually include agriculture, livestock and logging.

“If a project is established in a forest that was going to be converted into crop fields and local communities still need crops to eat, they will have to plant elsewhere. So direct leakage is the extent to which these types of activities change,” Sills said.

Market leakages, on the other hand, occur when the implementation of a carbon offset project reduces the supply of certain goods and services, resulting in higher prices that make it more profitable to deforest other areas for agricultural or livestock production.

According to Sills, this type of leak can also occur in other sectors. For example, if a country or company closes an oil well to reduce its carbon footprint, it can cause the world's oil supply to decrease.

When supply decreases but demand remains the same, the price of oil is likely to increase. This may cause competing companies to open new oil wells to meet demand, resulting in more greenhouse gas emissions.

"We have to grow food somewhere and produce energy somehow, so leakages will be inevitable unless and until we improve agricultural productivity or invest in renewable energy technologies," Sills said.

Credible baselines

REDD+ carbon credits are certified and tracked by nonprofit organizations like Verra based on a project's performance or, more specifically, “additionality”: the amount of deforestation prevented by a project.

Simply put, project developers establish a baseline scenario estimating the amount of deforestation that would have occurred without the project. That baseline typically assumes a continuation of historical deforestation trends.

The project developer then compares that baseline to the amount of deforestation observed in the project area to determine how much deforestation was actually prevented so they can determine how many credits were generated.

But the base case may not reflect what would actually have happened without the project, and project promoters are often tempted to forecast higher percentages of deforestation so that their project can claim credit for greater reductions in deforestation.

Project developers can select specific sites where the potential for deforestation is low, even though the surrounding region is undergoing rapid deforestation, in order to maximize their carbon credits, for example. This strategy helps developers meet their performance goals, but it doesn't actually prevent more emissions.

"This makes it easier for project developers to prevent deforestation when their sites are not in danger of being deforested in the first place," Sill said. "And while they 'protect' these sites, other more vulnerable areas of forest are being cut down."

REDD+ developers also often do not provide consistent, open-access information about their projects in a standardized format so that third parties like Sills and other researchers can verify the projects' additionality.

Sills pointed to his recent study of REDD+ projects in Peru, Colombia, Cambodia, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of the Congo as an example of this problem. While she and other researchers investigated a total of 26 projects, only 18 of them provided enough information on their assumptions about deforestation and “baseline” emissions to conduct a full analysis.

"The projects and companies highlighted in our studies are those that have done the best job providing the necessary information," Sills said. “This is a learning process and companies that provide complete information are becoming more vulnerable to criticism. But they are helping us learn.”

Worse recently announced which will now lead the process through which baselines are established for REDD+ projects, implementing national-level baselines produced by groups that use satellite remote sensing data to quantify forest biomass.

"It is a clear example of how the sector responds to science to improve the climate," Sills concluded.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/cmg/PB46SWBXB3DU47DSYRIKXGT4AE.jpg?w=75&resize=75,75&ssl=1)